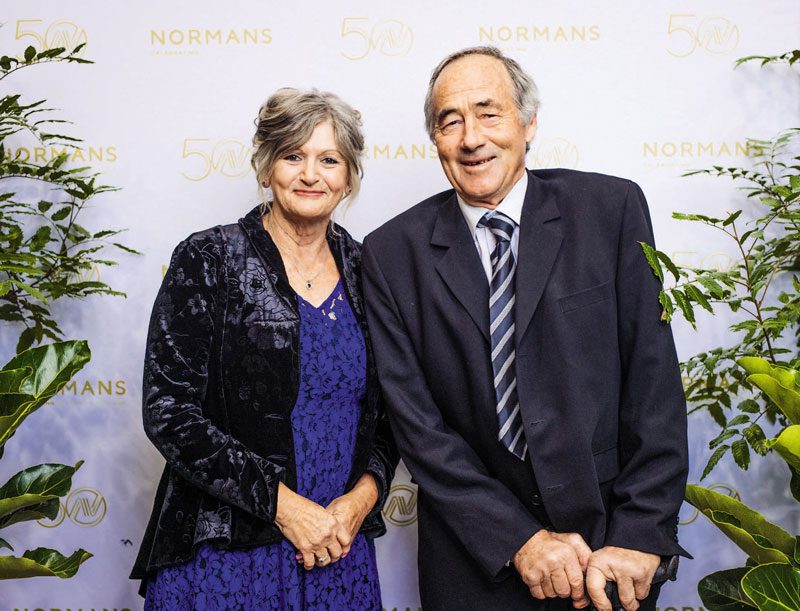

Saying ‘it’s all about the journey’ in reference to a half a century in trucking seems a little too synchronous as a metaphor, yet it epitomises what it takes to succeed in one of commerce’s toughest gigs. It’s 50 years this year since Charlie and Marie Norman began their transport journey and, looking at Morrinsville-based Normans Transport and Storage today, it’s obvious they chose to learn from all their journey had to teach

Charlie is one of those characters you can tell has you pegged when you’re still 50 metres away. The searching eyes, the shake from a hand you know instantly has closed a few crate doors, twitched up a few chains, strapped and covered its share of loads. There’s a natural cynicism cloaking an obvious eye for opportunity. It’s a safeguard when you’ve seen and experienced all he has. He’s dealt with them all. It’s unnerving. You’re unsure if he sees you as value or a waste of time.

“I’m not much for putting us out there, but they tell me we should mark the occasion.”

That’s the humility always present in those of his ilk. Ironically, it’s his breed the rest of us most want to listen to. Business success always starts and ends with the doers, and Charlie and Marie have ‘done’ a hell of a lot.

The Normans Transport story for me has been an observational one. A semi-local carrier you watch – you know them, but you don’t ‘know’ them. A couple of chance meetings over the years, once while riding around with other local carriers, and then years later, driving a truck yourself. I remember them, of course – he’s Charlie Norman. Understandably, he doesn’t. It’s one of life’s truisms that you’re often unaware just how much your own life’s effort moulds the lives of people you may never meet or know. Actions speak louder than words, and dogged tenacity looks like a role model a lot of the time.

Then there are the trucks, one in particular you remember made a young boffin sit up and take notice – a Scania LB141 8×4, but a single steer and rear tri with a lazy. John Robinson Carriers from Hikutaia had one; so did Normans at Tahuna. The Normans’ one had ‘North Island Livestock Transport’ on the front of the truck crate, and, of course, to a young, truck-hungry soul, ‘North Island’ inferred distance, and distance was cool… way cool.

You watch a company grow, and grow! Admiration without connection… until now.

“Not for the faint-hearted”

That’s Charlie’s recollection of the formative years. Again, like their peers of the era, the ‘gods’ tested his and Marie’s resolve relentlessly early on to ensure they had what it took, hammering home some of life’s valuable lessons.

But let’s start at the actual ‘go-line’ first. When Charlie came along, parents Doug and Alice owned and farmed Slipper Island, a 2.8km² isle roughly 8km southeast of the eastern Coromandel town of Pauanui. They later sold the island for £16,000, and talking to Charlie, you realise the entrepreneurial streak alive in him and brother John was certainly a direct generation-to-generation hand-me-down.

Charlie spent his first four years on the island before, as only he could put it, “We emigrated to Whangamata.

“School was a five-mile horse ride or walk away, and wasn’t an outstanding success, to be honest. Later at Waihi College my brother John and I were asked to leave and not return. John was 15, I was 13.”

In 1965, that left correspondence as the only option that turned out to be equally unsuccessful.

“By going to Paeroa and signing onto the dole, you had a job cutting scrub by 7am the next day for about $16-$20 equivalent per week. From there, I got a job with Alf Watchorn driving a bulldozer in the native bush locally, which naturally led to driving the log truck. I didn’t have a licence, so someone who had a licence but couldn’t really drive that well would sometimes come with me.”

Eventually, destiny prevailed and employment gave way to ambition. Two things are usually required to get started in business – an alarm clock and debt. The latter is normally unavoidable to the average person, and due to its close association with sleeplessness, quite effective at negating the need for the clock.

Charlie Norman doesn’t strike you as the type who ever needs an alarm clock, but he did need debt. In 1972, he borrowed $2500, $600 of which came via the trade of his parents’ farm truck on a 1966 Commer TS3 sporting a 117hp two-stroke ‘knocker’ diesel. Its name was ‘Black Pete’.

The truck was converted to a log unit with the maiden load of export logs to Mt Maunganui from Tairua’s Pepe Valley carted for the late Don Goodrick.

The track up the Eastern flank of the Coromandel to the Mount was torturous. “I could only do one load a day, and I loaded myself sometimes at the Tairua end with a dragline equipped with a scissor attachment.

“On one trip through the Athenree Gorge, the truck broke down. Not knowing how to fix it, I started walking to Katikati. I walked into the local carrier, Jeffcoat and Howse – my first meeting with Trevor Jeffcoat. He told me to get in the car and we set off to fix the truck. When we got there, Trevor said, ‘go find a small tea tree stick’. He jammed it in the two-speed diff and told me to come see him when I had enough money for a replacement spring.”

After a year, the Commer was traded in on a Dodge. A truck that still wakes Charlie up at night in a cold sweat. “It was a shocking thing. Let’s not talk about that.”

As soon as he could, he traded the Dodge on a 2624 Mercedes-Benz, and it was about this time that Charlie met Marie while carting logs off her parent’s farm at Coroglen.

Two years in, the log export market dried up. Logs not already on the Mt Maunganui wharf were left to rot, and because truck payments waited for no man, the need to find work – and quickly – was imperative.

Charlie and his brother John headed for Nelson, where they’d got wind of loads of beach logs as part of a selective logging operation near Reefton.

“We were unable to rent a car because we were too young. A friend of a friend who had some influence sorted that for us.

“We picked up a job at Radiata Transport on behalf of TNL and were due to start a week later. We headed for home to get the trucks organised and make our way back. There was no time to spare.”

The work carting to the chip mill in Nelson was good and paid well. Marie and Charlie wed after eight months, at which point they bought a 24’ caravan.

For Marie, things were a little tougher at the top of the South than it was for Charlie. ‘Outsiders’ found it difficult to get work in the local area, and the only thing available was general labouring in orchards.

The contract wound to a conclusion after 16 months. “When the contract ended it was a blow,” said Charlie, “but you get used to things coming to an end over time.”

The pair left the Richmond Motorcamp after selling the Mercedes-Benz truck, packing their Chrysler Valiant and caravan with their belongings and headed back north to the farm Doug and Alice now had in Opoutere, north of Whangamata.

The funds from the sale of the 2624 were invested into a venture with Doug and John in the Far North settlement of Okaihau. Unfortunately, after three years, that proved unsuccessful, leaving the pair with nothing but their car and caravan. They sold both to fund the purchase, as Charlie puts it, “of a worn-out, ex-Keveys MW ERF and 20’ trailer.”

“Craig Engineering in Kaikohe and I added ten-foot in the middle of the trailer, plus a third axle. This took two long nights of hard work.”

In the 1970s, road transport was heavily regulated and the railways were protected. In the cartage of general goods, road transport could not compete with rail beyond a radius of 40 miles (64km) from the road carrier’s depot. In the wake of the failed Okaihau opportunity and influenced by local carriers, the courts in the north deemed Charlie and Marie unfit to hold another Goods Service Licence in the area, and all company licences were dissolved.

“It was a stressful time. At one stage, Marie and our first-born Sandy were living under a tarpaulin alongside a creek, while I was driving a bulldozer in the back of Whitianga crushing scrub.”

From there, Marie and Sandy moved between both sets of grandparents, while Charlie lived in the truck, looking for anything that would turn a dollar.

“I joined a couple of real characters, one being Errol Sheehan, a truck driving semi-professional wrestler, a.k.a Dr Death, who many reading this will remember. We were carting hay from around the Waikato and Auckland regions to a feedlot south of Masterton, backloading potatoes to the Auckland markets. The spuds came up in the middle of the night if you get my drift.

“I was trying to run the truck, feed the family, and save enough to buy a set of stock crates. As I got close, I went and worked for Barry Gordon at Nationwide Stock Crates, where I painted several sets of new stock crates, as well as help build my own.”

Amidst the heavy regulation, certain categories of goods were exempt, things like frozen and perishable goods, as was livestock.

An opportunity to buy several livestock transport licences covering an area that stretched from Taupo in the south to North Cape presented itself. The licence domicile was Tahuna, a tiny rural village tucked against the southern end of the Hapuakohe Range midway down the western edge of the Hauraki Plains.

“We rented a house in Tahuna and went into partnership with my brother John and his wife Margaret, carting livestock and freight for Trailways Taupo, Kawerau, and Mount Maunganui. Ross Lyttle, Peter Smaile, and Stu Braithwait were all branch managers and we developed fantastic relationships with them all.”

Carting stock from the Waikato North forged connections with Silverdale- based Neville Brothers, resulting in the cartage of livestock south, as far afield as Waitara.

“Kelvin and Stuart Neville know how to work. They weren’t scared of the dark, that’s for sure.

“We even carted cattle to aeroplanes at Auckland Airport. Yearling Hereford heifers destined for Indonesia, loading 170 head at a time in old DC8s that had thirty-foot added to the fuselage. The airline was called Flying Tiger and was based out of the US.”

Relationships with local carriers were also established with the likes of Graeme Wright General Carriers, and Wayne Hughes’ Whitikahu Transport.

“One night, Wayne and I went to load cattle out of the Herekino sale yards in the Far North. While loading Wayne’s truck, which was blocking the road, along came a chap in a car. He was tooting and screaming ‘move your f%$#ing truck’. I went over to tell him we would only be a few minutes and he poked a double-barrel sawn-off shotgun under my chin. Around about then I got very diplomatic, and set off to tell Wayne ‘we really did need to move the truck’.”

“Sink or swim”

After the test of character that was the ‘70s, the ‘80s were simply sink or swim. That was a mindset the pair had learned a lot about, one they knew how to act on. You swim…relentlessly. Sinking is never an option.

In 1980 at a cost of $97,000, the ERF gave way to a brand-new Scania LB141, the truck that would help facilitate ‘swimming’. Whispering Breeze, the machine mentioned at the top of the story, housed a Scania 375hp V8 engine, with a 10-speed synchromesh transmission tucked up behind. An 8×4 with single steer and rear tri-set, it started life with a two-deck three-deck crate set-up, progressing to a three and three when the balance sheet allowed. It didn’t have a sleeper, but neither did it need one. This was not the time in the business’ history for sleeping, with the bulk of the next 10 years spent carting cattle from the Waikato, and as far north as Whangarei, to the Hellaby’s freezing works in Otahuhu, or sheep to Taumarunui.

“Tahuna to Gisborne, load, back to Auckland, then home was a regular Sunday drive,” Charlie says. “I remember doing 20 back-to-back loads from Gisborne to Kereone in the Waikato one time. One a day.”

Live cattle exports were added to the list of regular missions also, with Normans hiring local carriers to lend assistance.

When ‘Gypsy Week’, the annual share milker shift in early June each year arrived on the calendar, outside trucks were also hired in. While some were again local carriers, his old friends at Trailways in Tokoroa supplied most, a reflection of well-established relationships and goodwill.

Charlie had the trailer behind Whispering Breeze altered to a one-front and three-rear axle set-up with the rear axle an airlift. “It made turning in places like the East Coast hill country much easier. You could lift the rear axle and it would pivot on the lead axle of the tri. The 141 was a good machine and the only reason it wasn’t replaced with a 142 was Scania’s unwillingness to trade back then.”

Dalhof and King would, so for Viking fans, the first Volvo arrived in the fleet in 1984, the legendary F12 Intercooler model with its 385hp motor and 12-speed synchromesh transmission.

“Yes, I had a sleeper cab again, at last. The F Series were good trucks. Simple trucks that were easy to fix on the side of the road if you needed. That was my first dealing with salesman Leo Radovancich.

“I’ve always said any truck is only as good as the people selling it, and Leo was tops.”

Supplementing the stock work with loads of milk powder from the Morrinsville Dairy Co-operative to Mt Maunganui became an ever-increasing job towards the mid-1980s.

“Sandy had company by now too, Matthew and Corey had arrived, and Marie would come out to the yard in Tahuna at night with three sleeping kids in the back of the car and help take the crates off and wash decks.”

The freight work expanded steadily and carting empty pallets from Brimco Holdings Hamilton to various dairy companies in the Waikato, plus regular loads for Harvey Farms were also added to the roster.

“Jeff Brimley at Brimco helped our business significantly, as did Jeff Landsdown at Harvey Farms. Sadly they’ve both passed away now.”

After 13 years in the game, in 1986 the decision to sell out of livestock was taken. Driven not just by the rise of a new work profile, but also by changes in farming practices. Seasonal work that had once run for eight months in the year fell to four as beef and sheep farms gave way to dairy conversions. In a way, you could say Normans was moving to more consistent work at the other end of the dairy production supply chain.

But again, there was another storm to weather brewing just over the horizon. Charlie and Marie were approached by a local carrier to cart packaging on their behalf from Auckland to Hastings and Nelson. The Normans bought a secondhand Volvo tractor and built a brand-new B-train for the work.

“It was a three-year term that ended abruptly at the 18-month mark when the other party put a truck on himself. There was ‘no more work for Normans trucks’,” says Charlie. “I’m a handshake bloke, and that hurt us. Turnover plummeted from $70,000 per month to $20,000, and as anyone who lived through the ‘80s will remember, interest rates hovering around 26.25% had a significant impact on fixed costs. Our repayments were sitting at $11,000 per month.”

The Normans had one full-time driver who was hired out to local livestock carriers when there was no other work. In order to stay afloat, Charlie himself drove a bulldozer hired from a local farmer at times. Fourth-born Adam had also arrived, and Marie took on whatever work she could amidst the demands of a four-child household.

Although shockwaves rocked the business with the abrupt and unexpected end of the agreement, the South Island work had also served to open the door of opportunity. While carting south, Charlie was approached by the late Rob Lewis at the New Zealand Dairy Board (NZDB) about carting casein from the Golden Bay Dairy at Takaka to the Tatua Dairy Co-operative in the Waikato. “This was the start of our relationship with Tatua,” says Charlie. “The NZDB then asked if we could cart pallets of paper bags successfully by road to Takaka. The rail had it, but damages were an issue. It was tricky stuff to cart. If it wasn’t properly secured the bags would slide and end up in a hell of state.

“I was unloading at Takaka one day and chief engineer at the time Don Harwood asked if we could cart new milk vats to Takaka, again, ‘without damaging them’. Don has passed away now also, but this was the start of the milk vat cartage that we still do today 34 years later.”

Then came something new and innovative for the company, a Lees 20’ container side-loader.

“Rob Lewis asked me about putting a side-loader on to cart containers from the Morrinsville rail to the Morrinsville factory and return. This went well and soon we picked up work at Tatua also, uplifting containers and crossing the road to the local rail siding and placing them on wagons. This was previously done by the dairy company, transporting the bags on pallets by truck to the rail siding and then hand-stacking them into the appropriate containers.”

Shortly after, along came the New Zealand Co-operative Dairy site just up the road at Waitoa, with side-loader requirements also.

Eleven kilometres of near straight road separated three NZDB sites and each was a stone’s throw from the railway.

“The side loader was a significant piece of equipment in terms of the company’s future direction.

“Some days there were 60 containers between the three, and the side-loader wasn’t like the ones of today. It was operated by hand levers on one side, and the donkey engine was on the opposite side, so you were running all day.” Charlie shakes his head. “They were bloody long days.”

Packaging work to the South Island for the Dairy Board continued as did the casein home, and aside from the service levels Charlie was providing, that Norman innovate streak reared its head again.

“I had John Mudgeway at Dawson Engineering at Netherton build a B-train that had a lot of aluminium components. When everyone else was carting 22 tonnes, I was carting 31 tonnes legally, although I was right up to my tolerances.

“I was set up at one point. The cops were waiting for me near Nelson. They’d been tipped off, no question. They weighed and weighed, and eventually, as I drove off, they simply stood there shaking their heads.

“The guys at Takaka, in particular, loved it. They even asked me to do some loads of butter! I was reluctant, but they assured me if they froze it down hard and I double-covered it, we’d be right. They were right – it was fine. Carted on a flatdeck under tarps. Imagine an RMP [Risk Management Programme] auditor of today seeing that,” he chuckles. “Because of this, tarping’s rapidly becoming a dying art nowadays.”

The 1980s. A decade of continued challenge and resilience testing for sure, but also one where the pair were not afraid to open the door when opportunity knocked, resulting in the shift of focus from livestock to general cartage and containerised freight.

Breathe, and full steam ahead

The 1990s were more settled… well, sort of.

“We went into it with consistent work, which always helps,” said Charlie.

The first big move in the decade was in fact… a big move, into Murray Road, on the outskirts of Morrinsville. It was situated pretty much equidistant between Morrinsville and Tatua, which was ideal, far better suited to the changing nature of the business. But there were other, very 1990s reasons also.

“Road-user charges were bought from the post office and paid for by cheque. They were bought in 1000km lots at a weight you specified for the vehicle type. The nearest post office to Tahuna was 15 minutes away in Morrinsville and Marie was making multiple trips per day at times.

“Murray Road was a 10-acre greenfield site and we built a workshop, a kitchen lunchroom that was shared with the drivers, an office that was in the tyre bay and a small flat above with two rooms where the family lived for eight months while a house was built.”

‘Build it and they will come’. It applies to trucking as much as any other industry or discipline. The ‘it’ in trucking is more often than not reputation, and for that reason alone Normans Transport was flat out in a post-deregulation transport world. The company had the cartage of all packaging for the NZDB South Island sites. Imbued with the ‘Never say ‘No’’ service approach of so many of his era, Charlie’s efforts on one-off jobs like a ‘red-eye’ from Tahuna to Dargaville to Edendale over a weekend (to ensure the factory had stocks of the right packaging for the coming week) had contributed in no small part to the position they now found themselves in.

Rye straw was carted out of Canterbury back to Golden Bay, and there were loads of fresh fruit ex-Otago to the Auckland markets for Fulton Hogan Central. “They were on a tight timeframe,” Charlie recalls.

Of course, for any inter-island operation, the great bottleneck is the Cook Strait ferries. But they were more of an issue for Normans Transport than others. The reason was, of course, irritation within the railways over the loss of packaging work to the upstart blue and white fleet from the Waikato. As a consequence, making bookings was never an easy task.

Relief came, of course, in the form of Strait Shipping when it steamed onto the scene in 1992.

“The venture was launched by Tony Johnson, Doug Smith, Derrick Bouys, and Jim Barker to provide an alternative Cook Strait crossing,” says Charlie. “They bought a little ship called the Straitsman that had carted cattle and freight from Tasmania to its offshore islands and return. The cattle were carted below and above deck, and in heavy seas, the stock in the top pens certainly got a bath. They had the cattle ready to go from the start, but we were the first freight customer.

“They got laughed at in the beginning and battled the government, unions, and the Rail Ferry crews, but they had the guts to give it a go and persevere.

“The trouble with the Straitsman for us was the stern door at only 3.85m high. By that time we’d begun moving into curtain-side units and they wouldn’t fit. It meant we had to go cap-in-hand back to the Rail Ferries.”

There’s one Rail Ferry North to South crossing in that time Charlie recalls vividly. “There were 8.5m swells in the Strait and they couldn’t be bothered tying the unit down properly. As a result, it fell on its side and flattened a camper van. The whole mess slid across the deck three times, crashing into bulk-heads. In those days you could stay inside the truck and I was hanging on for all I was worth in the sleeper. I got out by kicking the windscreen out, only to be confronted with the deck at 38° and a giant coil of mooring rope sliding towards me. I dived back in just as it passed. The truck and B-train were buggered. It’s testament to the strength of those Scandinavian cabs…the pain it took. One of my nine lives went that day.

“Kiwi Rail didn’t even offer to bring the wreck back to the North Island, but Strait Shipping did.

“I had the B-train rebuilt at Dawson Engineering and put a new cab on the tractor. Initially, the insurance company wanted to repair it, so I told them if that was the case, I’d send them the ownership papers and they could just pay me out… it was absolutely stuffed.

“Once the Suilven arrived at Strait Shipping in 1995 we were right. At one point we were their biggest freight customer with 30 crossings per week on the inter-island work.”

In 1993, the company had built its first Dairy Board-approved warehouse covering 1100㎡ , and the first office staff member was also hired to assist Marie with administration and dispatch.

Change was rampant throughout the business. Back in the Tahuna days, the closest thing Charlie and Marie had to a computer was an adding machine that printed and a calculator, both located on that key piece of small-business office equipment, the kitchen table. Once daughter Alice had arrived, the accounts was a job that commenced once all five children were tucked up in bed.

“Evidently, the staff at the Dairy Board had quite a chuckle when our handwritten accounts arrived,” smiles Charlie.

But this was now the 1990s and fax machines, an answerphone, and cell phones with batteries half the size of the suitcase and questionable service – nothing’s changed there – had arrived. There was also an accounts computer, and even a road-user charges machine.

Tech was arriving in-cab too, and again the Normans ‘read the room’ impeccably. RTs gave way to cellphones, an essential given the size of the fleet footprint; likewise, fax machines were fitted to all South Island trucks so road users could be sent direct, and timesheets, waybills etc. back.

“One step forward, two back, two forward.”

Growing pains. The first decade of the millennium was one of huge change as the transport and storage business grew significantly.

“A large portion of the cartage in this period was focused on the South Island. It was only five years since we’d built the Murray Road warehouse, yet we’d outgrown that site. We were at 15 trucks by that stage. It was then that Marie and I purchased the site at Avenue Road in Morrinsville for the new depot and head office. We moved in there in 2001.”

The demise of the Dairy Board and arrival of its successor Fonterra in 2001 saw a logistics management cell formed and contracted to the new entity. Normans Transport and Storage chose not to join Fonterra’s logistics group, and although that resulted in downsizing for a spell, it certainly didn’t mean the end of servicing the dairy industry, or the South Island.

The Dairy Board South Island packaging work had meant Charlie crossed paths with Westland Co-op CEO Hugh Little.

Hugh had asked Charlie why their carriers couldn’t get milk powder from Hokitika to Nelson without spilling it along the road, and could he do a better job?

“I knew straight away why; I’d seen them securing it, and I’d seen where it ended up. He gave me a trial load, which I did. Then he asked me if I could stay down and carry on for a week? I rang Marie and said ‘I’ll be a bit late home’.

“We ended up carting to Christchurch over the Arthurs Pass, and back to our Morrinsville store for distribution. Hugh was someone I had great respect for.

“When the Fonterra thing happened, Tatua and Westland Dairy Co-op remained independent, so we just happily carried on.”

Over the next three to four years, the South Island work continued to grow again, considerably.

“General freight, agricultural machinery, dairy products, they were all in there,” says Charlie. “There was a real mixture. We carted wine barrels, even yacht masts and an engine shroud for a 747 amongst other freight. We went as far south as Invercargill and usually backloaded dairy product from Westland Milk Products at Rolleston.”

As a result, the fleet again expanded to 26, clawing back much of the ground lost with the Fonterra decision.

In 2002 Adam Norman joined the business sweeping the floors, helping in the workshop, and moving on to working in the warehouse. In the years following, he worked in all facets of the company, and at 37, is now the manager and a shareholder in the business.

After 15 years servicing the inter-island freight scene, the decision was made to sell that side of the business to the late Jim Barker’s Freight Lines in 2006. “Jim was a shrewd businessman, but we always got on well,” says Charlie.

“Over the years, we learned that not many carriers could be trusted to keep their word, and do a good job. There are the exceptions of course, and I’ve talked about them, but I want to mention John and Cheryl of Opzeeland Transport also. Great people that we continue to work with to this day.”

With the sale of the inter-island work to Jim, the fleet again reduced back to 21 trucks but there was a plan at play. Freight Lines was building its inter-island business, and the Normans could see their Morrinsville location, in the heart of the Mt Maunganui/Hamilton/ Auckland ‘golden-triangle’, had huge potential.

They were right of course. The depot at Avenue Road developed rapidly and the company’s storage arm expanded to include four separate RMP-accredited food-grade stores covering 6000㎡ .

“As the warehousing capacity increased we were able to pursue new opportunities connected to container transportation and distribution, including our first MPI bioecurity approved transitional facility for the devanning of import containers. Both container and general transport soon required additional units, again resulting in expansion.”

Milestones, mishaps, and miracles

In 2012, Charlie and Marie celebrated 40 years in business. The fleet was assembled and there were events held to mark the occasion. Little did the family know what lay just around the corner.

“Yeah, I’ve always had a thing for logging. It goes all the way back to 1972 and the Pepe Valley days. But in March 2012 I was logging a private block of land and suffered a mishap that almost killed me. I was left with no feeling below the waist and partial paralysis. It was certainly life-changing for both myself and Marie.”

Charlie attributes the fast and professional response from driver Don Mckay, his mate Trevor Newport, the Tahuna Volunteer Fire Brigade, a local nurse, and the Waikato Westpac Rescue Helicopter with his survival at the scene.

“Then there’s the Emergency Department at Waikato Hospital. Without all of them, I wouldn’t be here. Myself, Marie, and the whole family are forever grateful to everyone for their help that day. Each year, we support the Tahuna Volunteer Fire Brigade and the rescue helicopter. It’s something we can give back.”

It would be fair to say setbacks were nothing new for the Norman family, neither was overcoming them. Despite the accident, the business remained full steam ahead and the decision to focus on the country’s logistical hotbed was paying off.

Avenue Road was no longer able to contain the requirement and in 2014 a brand-new 14,000㎡ warehouse was opened in Te Rapa, dramatically expanding the company’s capability. The facility incorporated food-grade storage, and a further Biosecurity transitional facility.

Avenue Road didn’t miss out on all the goodies though, gaining an additional warehouse and load-out canopy, increasing that site’s footprint by 1650㎡ . This addition now took facilities at the 6.5-hectare Morrinsville site to five warehouses, three loading canopies (12,000㎡ ), a three-bay workshop, the administration complex, and parking for 35 trucks.

New buildings and additions to Avenue Road weren’t the only story in 2014. Expansion in all areas meant Marie needed help with the Food Grade Compliance required by MPI, so Alice Norman stepped in and joined the business that same year, and today sees to all the regulations and audits.

Today there are 80 staff employed across the various divisions. It’s all a long way from the humble yard at Tahuna, eons from a 2624 Mercedes-Benz and 24’ caravan in the Richmond Motorcamp ground near Nelson, and unfathomable if you hark back to a TS3 Commer called Black Pete heading for the Mount with a load of logs and a tea-tree stick jammed in the two-speed. Or is it?

Spend a couple of hours with Charlie and Marie and what resonates the most is never, ever forget where you came from, and the toil so many both inside and outside the family have put into getting the business to where it is today.

“You must never take anything for granted,” says Charlie. “I hear people talk about being in hard times and I say, ‘I have a cure for that’. ‘Do you?’ they say. ‘Yep. Go to bed an hour later, get up an hour earlier, and get stuck in. It’s always worked for me’.”

Change. It’s the only real constant in life, and Normans Transport and Storage in 2022 is testimony to the fact that if you’ve got the right mix of ambition, energy, and malleability, then crisis, change, and opportunity often appear as one and the same. However, philosophy, culture, and principle are ours to keep just as they are – in perpetuity if we want. Build the company you want on the foundations of culture and principle you decide.

Principled flexibility. In 2022 it’s as rare as the proverbial rocking horse… Yet it’s exactly what is required to get a start-up going and have it looking like Normans Transport and Storage half a century later. The customer base today reflects the respect the Norman name has, and some have been on the ledger for more than 30 of the 50 years to date. Likewise, suppliers. Business in the Norman sphere is about the lasting principles of commercial relationships.

Charlie Norman is renowned for an uncompromising attitude to service and customers, and everyone who knows him well will tell you he’s a great bloke, with gun barrels as straight as they come. As more than one party told us in the process of gathering and chatting about this piece, “You won’t be left wondering with Charlie.” You know that from the moment you meet him, before he’s uttered a word. And in the end, isn’t that the only type of person we actually want on our contact list?

Of course, no man lives forever; many have died trying. For an enterprise such as Normans to see out the next 50 years, the big question at this juncture is always succession. Any number of great businesses, both local and overseas, have fallen on the sword of succession. In this story, that question appears well-answered.

At 70, Charlie still works everyday either at the office, from home, or on the road in his ute. Likewise, Marie isn’t far away either, and that might be attending meetings, helping with the grandchildren, and running their 30-acre lifestyle block.

Adam’s a bit scary, to be honest. He’s tall and of slender build and as he approaches you down the hall his piercing eyes have you pegged 10m prior to shaking hands. He has time for what you are there for. Somewhere here there’s a chip off an old block, maybe?

In truth, handing on the reins takes bucket loads of humility on the part of the founders. It is, at the end of the day, the greatest measure of who they are. It is the final testament that you really didn’t forget where you came from; the same humility that fuelled Charlie’s reluctance to have the half-century marked in the magazine.

“…but they tell me we should mark the occasion,” were again, his words.

When you’ve grown something so worthwhile that’s helped put the food on not only your table, but the tables of so many households over five decades, it’s okay to cut yourself a bit of slack and celebrate with those who shared the journey and helped make it happen.

The truth is, not everyone has what it takes to grow a business, to make sacrifices albeit with the family; to put the customer first and get the job done… because if you take too long, someone else will.

NORMANS TRANSPORT AND STORAGE AT 50 YEARS – 2022

Staff

80

Sites

• Avenue Rd, Morrinsville

• Arthur Porter Dr, Te Rapa

Fleet

10 skelly trucks

6 side-loaders

16 freight units

4 flat decks

3 crane trucks

2 log trucks