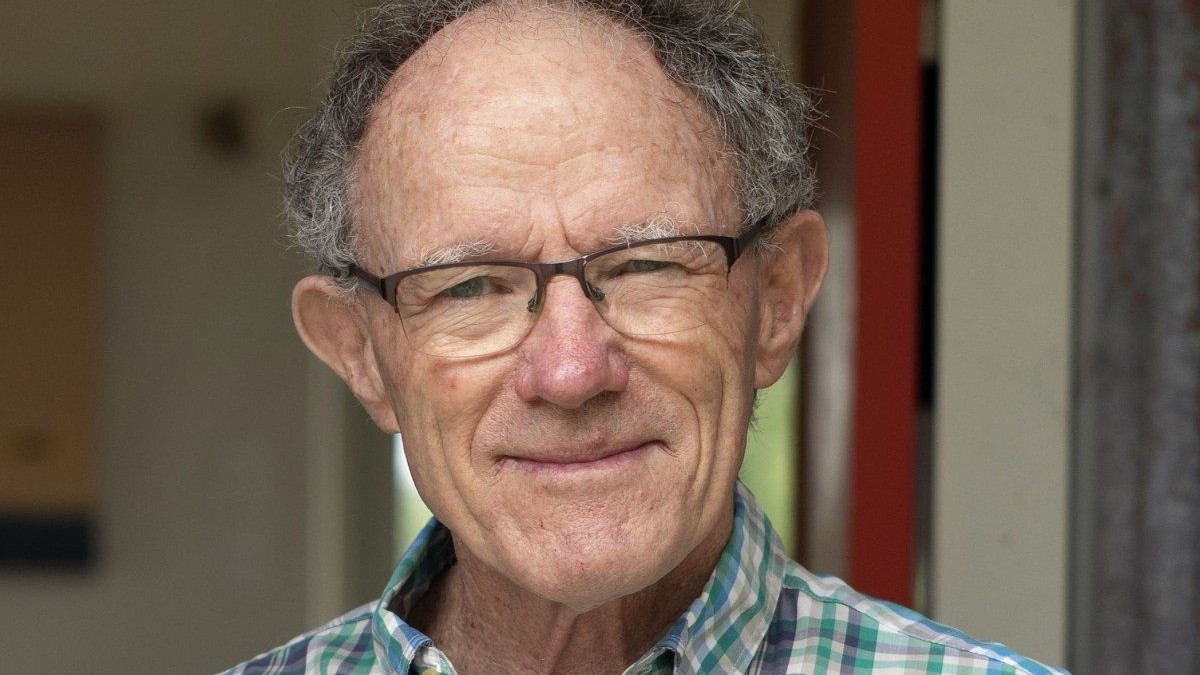

Lindsay Wood explores the challenges he sees with futureproofing our transport infrastructure.

London Underground’s famous ‘mind the gap’ announcement is a quirky example of the very long reach of infrastructure decisions.

Why is it even needed? Because carriages are straight, but many underground platforms are curved, causing dangerous gaps at some doors.

Why are platforms curved? Because many tube lines follow the roads above. When were the roads formed? Up to 2000 years ago, when Romans occupied Britain.

We can’t expect Julius Caesar’s transport minister to have envisaged how London would work two millennia later, but it does highlight the long-term implications of infrastructure decisions.

And right now, we’re facing transport decisions on steroids, with the Cook Strait ferry upgrade in turmoil, expansive plans to create ‘world-class’ roads, and shuffling the deck before dealing a new hand for railways.

Factor in badly neglected highways and frame it with the monumental need to slash fossil fuel usage, and it’s hardly surprising we have uncertainty about how far current plans are looking ahead and how far they are looking backwards.

For example, the promise of 10,000 EV chargers seems like visionary planning to propel the switch to EVs. Yet, by slashing incentives, the government has effectively reversed the policy settings that made Norway the poster child of EV uptake: with strong incentives but haphazard charging infrastructure, Norway’s EVs now exceed 80% of car purchases.

Perhaps more concerning is that heavy transport is barely mentioned in National’s main transport document and is entirely absent from that on charging infrastructure. As New Zealand Trucking Media editorial director Dave McCoid told a Nelson fleet management group last year, the lack of such infrastructure might prove an Achille’s heel of electrifying New Zealand’s heavy vehicle fleet.

And Port Nelson has a futureproofing anomaly that illustrates the need for government intervention: a major mains upgrade in anticipation of charging HGVs got the thumbs-down because of charges levied on the size of futureproofing cables, not the power they deliver.

There’s also the real danger the international mineral sector won’t come close to supporting the widespread electrification of the global vehicle fleet. It’s no accident that China seeks to dominate world lithium supplies, and Norway just approved controversial offshore exploration for critical rare earth elements.

“But hang on!” I hear. “There’s more to transport infrastructure than EVs.” And to be sure, there is.

But if highway planning is based on dramatically expanding EV numbers, while there’s a serious possibility that won’t happen, then how we think about highways and decarbonising transport may need overhauling.

To give credit where it’s due, thumbs-up for policies exploring congestion charging. However, many proposed roads hope to tackle congestion with the approach that caused it (plan highways that encourage new housing; find new highways are soon blocked with extra commuters; plan expanded highways that, in turn, attract more housing…).

So maybe we should press pause on highway planning until we mind the gaps?

Take Hamilton’s Southern Link, with National’s policy proposed “21km of state highway, three new bridges and 11km of urban arterials”. At the same time, Waka Kotahi/NZTA recommended making the best of the existing system and only building local roads already in train.

It also remains a mystery that successive governments claim to focus on efficient, cost-effective infrastructure yet spend fortunes on inefficient highways sized so more people can sit alone in their cars. These are the very cars creating gridlocks that impede efficiency for commercial transport operators and bringing big dollar and emissions price tags.

So, what might this mean for the climate? As slashing fossil fuels is mission-critical, it means ‘mind the gaps’ all over the place. There’s one between what we’re told new highways will do and their likely impact; another between policies to decarbonise the private and the commercial fleets; there’s one between current EV strategies and those proven to work overseas; and mineral supply challenges might even mean gaps between highways being planned and those we actually need.

And we haven’t even looked at the gap between the minimal time we have to get our decarbonising act together and the time until current policy settings will have real impact.

Read more

Scoping Scope 3

0 Comments4 Minutes