Heavy Truck Incentives quickest road to reducing emissions

Green hydrogen’s place in reducing carbon emissions from New Zealand’s transport fleet is indisputable. Hiringa Energy lays out the maths, responding to the Ministry of Transport’s recently released New Zealand Freight and Supply Chain Issues paper.

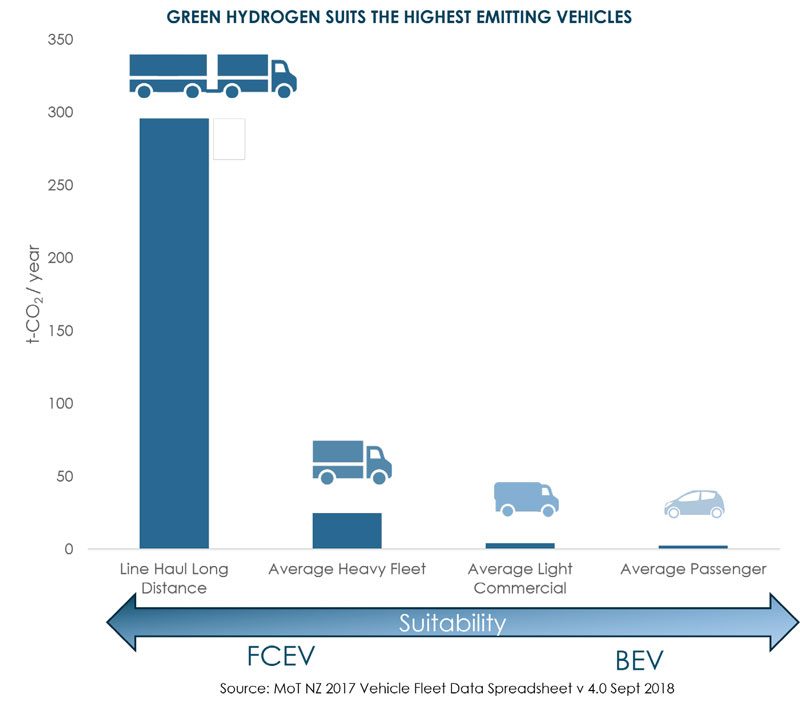

Transitioning the heavy-trucking fleet to zero-emission technology presents a vital opportunity for reducing emissions associated with our critical supply chains. The key focus is on heavy vehicles because they make up 23% of New Zealand’s transport emissions. While light vehicles currently produce the most emissions, it will be trucks that generate the most by 2055 without further intervention.

Other forms of heavy transport – aviation, rail, coastal shipping, and ferries – will also benefit from hydrogen technology, and developments are underway. But heavy trucks are the ‘low hanging fruit’.

Fleet operators need incentives

The bulk of heavy-truck fleets are owned by a couple dozen commercially minded fleet operators (as opposed to millions of passenger vehicle owners). The heaviest trucks drive the most kilometres and emit more than 150 times more CO2 than the average passenger vehicle.

Replacing these heaviest trucks with green hydrogen fuel-cell electric trucks (FCEV) prevents approximately 300 tonnes of CO2 from entering the environment each year depending on payload (based on 225,000km per annum for currently operating line-haul freight trucks).

Ultimately, this vehicle technology will be cheaper to produce and maintain than the internal combustion diesel engine due to its significant reduction in parts. The problem is that while prices are reducing, the capital cost of zero-emission heavy trucks is still high. With New Zealand purchasing about 6500 heavy vehicles yearly, fleet turnover will take several decades. However, every purchase of a heavy vehicle with an internal combustion engine (ICE) locks in up to 20 years of diesel emissions.

Why green hydrogen

Green hydrogen is seen by many within the heavy-freight industry as the preferred zero-emission mobility technology because of the operational efficiency benefits it offers. These include maximising the payload able to be carried due to the fuel’s high energy density and, therefore, revenue per trip; refuelling being similar to refuelling of diesel; and the long ranges of green hydrogen vehicles, cutting out EV recharging or fleet rotation issues.

The rapidly rising diesel price is a stark reminder of how exposed New Zealand is to geopolitical influences. Once online in 2023, the green hydrogen produced at Hiringa stations in Te Rapa, Tauriko, Wiri and Palmerston North won’t be impacted by what’s going on in global politics because it’s a locally produced fuel made from wind, rain and sunshine.

Accelerating freight decarbonisation

The government has multiple ‘levers’ at its disposal that can be pulled to accelerate freight decarbonisation. One example is a capital cost barrier reduction through a ‘Clean Truck Discount’ scheme.

If a small portion of the cost of new diesel trucks was used to discount the cost of new zero-emission trucks coming into the country, it could go a long way to reducing the up-front cost barriers associated with zero-emission trucking.

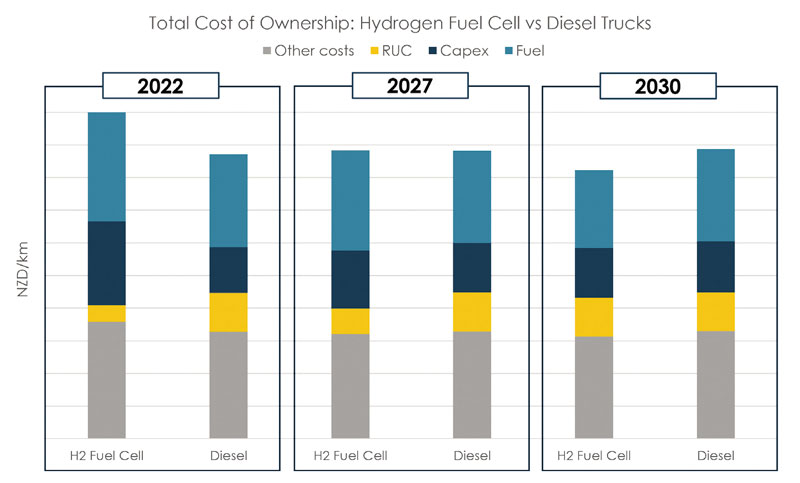

But this isn’t the only lever. The total cost of ownership for a truck depends on several inputs, as seen from Figure 2, and many levers could be combined for maximum impact. Relying on one incentivisation scheme alone is risky, so the government needs to consider a variety of tools:

a) Capital cost support via EECA’s Low Emission Transport Fund or similar

b) Exempting zero-emission heavy vehicles, including combinations from Road User Charges until 2030 (currently, exemption is only for prime mover up until 2025)

c) Allowing increased weight for zero-emission heavy vehicles under the VDAM Land Transport Rule

d) Streamlining of zero-emission vehicle compliance

e) Providing a fuel rebate on green hydrogen produced and supplied to the transport market

f) Developing a Low Carbon Fuel Standard similar to international examples, that is designed to decrease the carbon intensity of fuel and provide an increasing range of low-carbon and renewable alternatives over time

g) Accelerated depreciation of zero-emission trucks

h) Government procurement requirement of zero-emission freight services

With the government’s support, TR Group is importing 20 hydrogen fuel-cell heavy trucks, which will be leased to many of New Zealand’s largest truck fleet operators from early 2023. In addition, Hyundai has already committed to having five of its Xcient FCEV heavy trucks on New Zealand roads, with the first two already in the country. So this technology is not coming to market sometime in the future; it is ready now.

A key enabler for fleet operators has been the RUC exemption available until the end of 2025. RUC costs associated with type 309 vehicles are approximately 30 cents/km, with a B-train being another 22 cents/km. These combine to cost operators at about 52 cents/km. At 120,000km per year, this costs about $62,000.

Removing this cost helps close the gap between diesel-powered and zero-emission trucks in the short term until economies of scale kick in and the total cost of ownership of a zero-emission truck is less than a diesel truck and no longer requires exemptions or incentives. Hiringa Energy sees this crossover point being between 2027 and 2030 (this is also demonstrated in Figure 2).

Government investment would have a significant and fast impact on emission reduction if it was focused on decarbonising the heavy fleet. Trying to convince millions of car owners to go electric will take a long time, time that we can’t afford to lose.

Dion Cowley is the project development and public sector lead for Hiringa Energy, a Taranaki-based producer of green hydrogen and developer of the infrastructure to deliver it.

Dion Cowley is the project development and public sector lead for Hiringa Energy, a Taranaki-based producer of green hydrogen and developer of the infrastructure to deliver it.