Electric Light Distributor

A silent 400km drive from a colourful English seaside town to London gave Will Shiers time to ponder the future popularity of battery- powered trucks.

Nicknamed the ‘Las Vegas of the North’, Blackpool in the northwest of England, is home to the illuminations. For more than 100 years, British holiday- makers have flocked to this seaside town to eat fish ‘n chips and marvel at the 10km of colourful lights (us Brits are easily impressed).

Thanks to the Thunberg effect, Blackpool, like the rest of us, has had to clean up its act in recent years, and today the one-million lights that make up the illuminations are powered by green electricity. This, to my mind, made it the perfect place for a photoshoot in a fully electric Volvo eFL 16.7-tonner. Plus, like the rest of my countrymen, I’m rather partial to battered cod and chips.

Firstly, I’ll tell you now that I’m not convinced that battery power is the way to go for commercial vehicles, at least not yet. As you well know, a Euro-6 diesel engine is incredibly clean, and in London (where my journey will finish), the tailpipe emissions from a modern truck are cleaner than the air people breathe. Modern trucks are quite literally cleaning up the city. But whether I like them or not, zero-tailpipe-emission trucks are coming, and fast too. Last year the British government published its Ten Point Plan’ for a green industrial revolution, which stated that trucks with GVWs between 3.5 and 26 tonnes must be ‘zero emissions’ by 2035, and larger vehicles by 2040.

That’s all well and good, but these are just words. By this time next year, I want to be driving around in a Bentley Flying Spur with Georgia May Jagger by my side, but just because I’ve said it, it doesn’t mean it’s going to happen. Several things must happen for electric trucks to be purchased in the numbers Prime Minister Boris Johnson wants.

First up are trucks – lots of them and in numerous configurations. In this respect, the vehicle manufacturers are starting to deliver the goods. While there are still some major gaps in their model line- ups, most do offer at least one zero-tailpipe-emission model. It’s interesting to note that it’s the old-guard truck- makers who have been first to market, and not the start- ups. Where’s the long-awaited Tesla Semi that we heard so much about in 2017?

Volvo is more advanced than most. Now, British hauliers can drive away in either an eFL or eFE. This September, the company will put its eFM and eFH into production, and next year they will be followed by the eFMX construction range.

Second on the list is a significant extension to the current achievable ranges. The distance between Blackpool and London is 400km, but the eFL has a claimed range of 225km (in fact, I managed well over 240km between charges in this unladen truck), which meant a scheduled stop for recharging halfway.

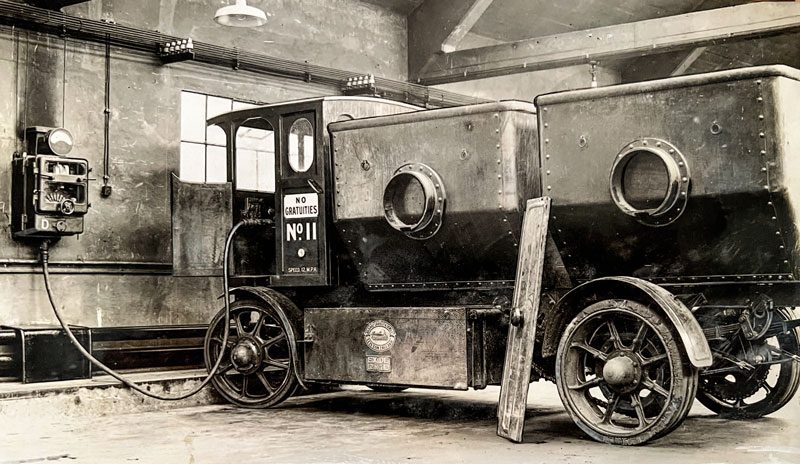

Now don’t get me wrong, 225km is perfectly respectable for an urban distribution truck such as this, which is likely to return to base each night. But think how many batteries you’d need in a long-haul tractor to get a half-decent range. What we need is a breakthrough in battery technology, and quickly too. It’s interesting to note that at the start of the last century, there were numerous electric trucks in production. In fact, there was a Betamax/VHS-type of battle going on between electric and internal combustion engines (ICE). Just think how far advanced battery technology would be today if ICE hadn’t won.

Next up is affordability. Electric trucks are eye- wateringly expensive, which acts as a massive barrier to hauliers looking to make the switch. A truck like this costs close to four times the cost of an ICE equivalent. How many hauliers can afford that level of investment? Instead, what will happen is the big players will buy a handful, and of course shout about their green credentials to anyone who will listen, while their diesel fleet does the hard graft. There is no doubt that the price of electric trucks will fall in the future, but not to ICE levels. The expensive bit is the batteries, and these aren’t really affected by economies of scale, as they are packed full of the same precious metals the whole world is currently demanding.

This leads me neatly onto the fourth thing on the list – incentives. The experts tell me that a cost parity with diesel is coming, and with urban-distribution vehicles it could be as soon as a few years away. But it’s a lot further down the line for long- haul. One way this could change overnight is with the introduction of decent financial incentives. So, what are the current British incentives? Well, for starters, there’s that warm fuzzy feeling some might get from the knowledge that they’re supposedly doing their bit to help halt global warming. And, of course, there’s the marketing opportunities associated with applying a ‘look how green I am’ livery to your truck. All 2- and 3-axle electric trucks are allowed to carry an additional tonne (or 700kg in the case of this 16-tonner on account of the axle weights) in Britain. Up until 2025, all electric vehicles are exempt from London’s Congestion Charging Scheme ($30 per day), and they’re road-tax-exempt too. There is also a small subsidy scheme, but it’s complicated and paltry compared with those offered by some other European countries. A deeper funded incentive scheme would boost the demand for electric trucks overnight.

And now for the big one… Infrastructure! According to the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), Britain needs 2450 electric truck charging points by 2025 and 8200 by 2030. On my drive to London, I initially attempted to charge up at a motorway service area (MSA), only to find that while there’s provision to charge cars, it doesn’t have any truck chargers. And it’s not alone. In fact, at the time of writing there isn’t a single charger in any of the UK’s 111 MSAs. Of course, I could have taken up three car charging bays, but instead I did the courteous thing and made a detour to a Volvo dealership. There, it took three hours to fully charge the truck on a 50kW charger. Incidentally, a typical MSA today has a 1MW connection, but according to British utility company the National Grid, they will need 20MW to charge electric trucks – which is the same as a mid-size town.

Last but by no means least is green electricity. I make a point of referring to battery electric vehicles as ‘zero-tailpipe-emission’ vehicles, because unless they’re charged with green electricity, they’re not zero emission. Less than half of the electricity produced in the UK currently comes from renewables. Clearly, your electric truck isn’t as green as you think it is when fossil fuels are being burned to produce the electricity that charges it.

It’s no wonder that sales of electric HGVs in Britain are estimated to be 14 years behind those of cars. And unless the points mentioned here are tackled, I don’t envisage anything changing soon.